In her Introduction to Scientific American‘s special issue on “world-changing ideas,” editor in chief Mariette DiChristina describes an address Google founder Larry Page recently gave at a conference for scientists, science journalists, and other quest-for-knowledge hangers-on.

In her Introduction to Scientific American‘s special issue on “world-changing ideas,” editor in chief Mariette DiChristina describes an address Google founder Larry Page recently gave at a conference for scientists, science journalists, and other quest-for-knowledge hangers-on.

“Is what you’re doing going to change the world?” Page challenged conference-goers to ask themselves. “If not, maybe you should be doing something else.”

While DiChristina quotes Page approvingly, I feel a little resistance rising in myself. I want to remember that “change” is a neutral term�and even in a speedy digital age, it may take time to tell whether any given innovation is a change for good or ill.

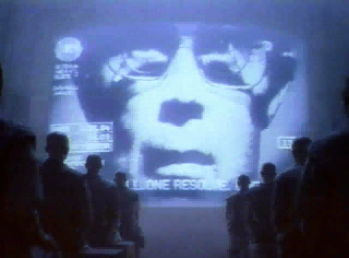

“We are bewitched,” writes John Thackara at Design Observer, “by just one element of the world around us: its digital overlay. Thus bewitched, we waste astronomical amounts of energy and resources without even realizing it. Thus bewitched, we are destroying the biosphere upon which all life, including our own, depends.” Thackara evokes the example of the moai of Easter Island, the famous giant sculptures that gaze grimly landward from the island shores. The elites of Rapa Nui, as Easter Island is known in its aboriginal language, conceived such a mania for carving and erecting moai that they used up the tiny island’s resources, precipitating the collapse of their culture. Thackara wonders: is the Web our moai�our magnificent, doomed folly?

The question intrigues me, although I’m not sure that I’m willing to go as far as Thackara does. His comments refer to Doug Rushkoff’s latest book, Program or Be Programmed, which recommends the acquisition of expertise and a spirited and practical engagement with technology. Thackara would prefer that we remember instead the vast world that stretches beyond the digital. I think Thackara reads Rushkoff wrong; Program or Be Programmed is about learning to hold tech more lightly, that we might better judge the weight and powers of the tools in our hands. As Kevin Kelly points out, just because we find technology’s revelations fascinating doesn’t mean that we must blindly do its bidding.

I’m persuaded that throughout history, life gets better whenever people intensify their sharing of images, stories, and ideas. At the same time, however, I’m turned off by the mandate of Page’s innovation ethic. It’s the bright-green, worldchanging, technofuturist ideology of the TED conferences: whiggish about the past, utopian with respect to the future�too often forgetting that the past, like the future, is largely the sum of unintended consequences.

In the extent and diversity of our dependence on technology, humankind is unique. But we’re also singular for having wrested moments of purposeless peace from amidst the brutal struggle of living on Earth. Daydreaming, idling, flights of fancy and curiosity: these too have merit, even if they don’t cure cancer or make a mobile app a little bit friendlier. If our every action is put to the test of “world-changing,” we risk making tools of ourselves.

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More