There has been, from the outset, something about (WikiLeaks’) activities that goes way beyond liberal conceptions of the free flow of information. We shouldn�t look for this excess at the level of content. The only surprising thing about the WikiLeaks revelations is that they contain no surprises. Didn�t we learn exactly what we expected to learn? The real disturbance was at the level of appearances: we can no longer pretend we don�t know what everyone knows we know.

However, it is a mistake to assume that revealing the entirety of what has been secret will liberate us. The premise is wrong. Truth liberates, yes, but not this truth. Of course one cannot trust the fa�ade, the official documents, but neither do we find truth in the gossip shared behind that fa�ade. Appearance, the public face, is never a simple hypocrisy. E.L. Doctorow once remarked that appearances are all we have, so we should treat them with great care. We are often told that privacy is disappearing, that the most intimate secrets are open to public probing. But the reality is the opposite: what is effectively disappearing is public space, with its attendant dignity. Cases abound in our daily lives in which not telling all is the proper thing to do. In Baisers vol�s, Delphine Seyrig explains to her young lover the difference between politeness and tact: �Imagine you inadvertently enter a bathroom where a woman is standing naked under the shower. Politeness requires that you quickly close the door and say, �Pardon, Madame!�, whereas tact would be to quickly close the door and say: �Pardon, Monsieur!�� It is only in the second case, by pretending not to have seen enough even to make out the sex of the person under the shower, that one displays true tact.

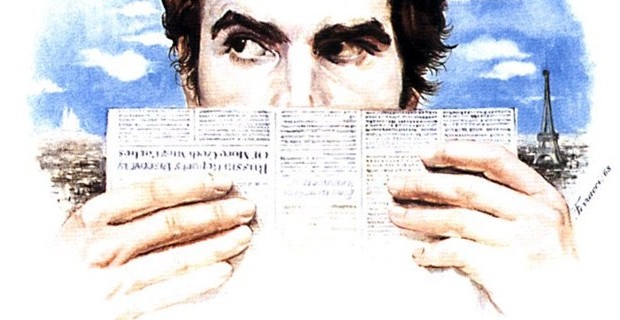

�Slavoj �i�ek, in an essay entitled “Good Manners in the Age of WikiLeaks” in the January 20 London Review of Books. The Slovenian philosopher argues that it’s not for its exposure of secrets, but for pointing up “the shameless cynicism of a global order whose agents only imagine that they believe in their ideas of democracy,” that WikiLeaks is hated by the powers-that-be. Quoting Marx, �i�ek observes that government has become “the comedian of a world order whose true heroes are dead.” It’s worth making explicit the parallel that �i�ek implies between the ebbing of government’s moral mandate and the peril of the person in light of Internet culture and the social media: in our strident claims to privacy rights, we photo-senders and status-sharers ask one another to imagine we believe in rights we’ve already waived. We pretend that Facebook is private, when in fact it’s privative; the tears we shed are those of a clown.

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

if truth does not set us free, or if secrecy does not bind us then there is little to be learned from history. whether one deceives with a lie or a secret the effect is the same, confusion of thought and evential chaos of action.

if logic is to be employed, the facts need to be true. a balanced conclusion occurs from rational thinking and not emotive ideology. subjective reaction is hasty from belief while objective analysis is contemplative form deduction.

no matter why or how one dresses up a lie or a secret , under its apparel, it is a beast with the same nature and the same consumptive appetite for truth.

“whether one deceives with a lie or a secret the effect is the same” – james fingleton wild

It seems to me that the problem intimated by Zizek is that there is a deception at the level of “truth”, the consequences of said deception function in the same way as that of a lie, ala Zizek’s criticism of “fetishistic disavowal” or in other words, cynical ideology; an example that illustrates this point is that of the recent Wikileaks saga: We assume that representatives of government act one way publicly and another privately, for example in respect to foreign relations, for our benefit. Wikileaks are said to expose this hypocrisy (and thus force the flow of information, transparency of government and so on), yet, isn’t it so that we act “as if” our representatives do so for our benefit and yet spontaneously also hold them accountable for concealing the “truth”? Isn’t then the problem of the matter that the apparent consequence of any Wikileaks expose` is without might? We know very well that our representatives play the game, yet in our social effectivity we act as if they do not, a direct parallel with how our representatives act in regards to foreign policy. Thus it is not as @james fingleton wild suggests, that having deduced truth or having exposed a secret that we obtain “freedom” but rather that the real consequence of Wikileaks is that it is another potential catalyst to short circuit cynical ideology, that is to say that we may no longer be able to act as if we don’t believe.