Last Friday, NASA launched a new spacecraft on a bold mission to spend the next six months studying the distribution of life in the universe. In keeping with the enormousness of its mission, the unmanned craft has a cumbrous title: Organism/Organic Exposure to Orbital Stresses, O/OREOS, for short.

It’s probably time to mention that the spacecraft is the size of?well, of a packet of Oreo cookies.

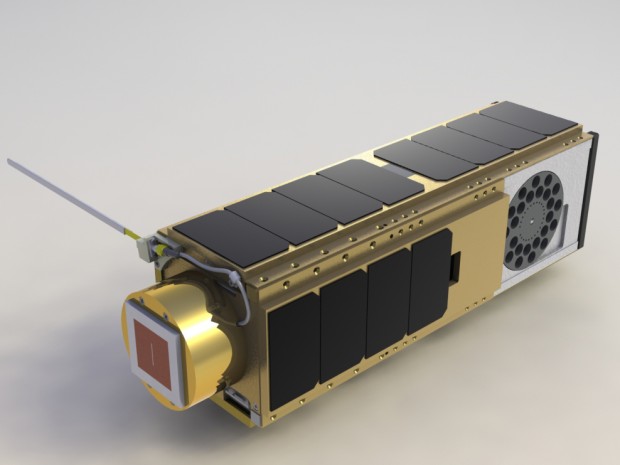

O/OREOS is a “nanosatellite,” a spacecraft weighing between one and ten kilograms (or two to about twenty pounds), designed to carry out highly specific experiments or measurements. At about ten pounds, O/OrEOS is a midsized nanosatellite, the first to carry two experiments aloft. In one experiment, the craft will monitor the health of an onboard colony of microbes; the other experiment will monitor changes in a mixture of organic compounds deeply tied with the composition of life on Earth. Both experiments seek to answer questions about the capacity of life to withstand extremes of temperature and radiation in space.

Festooned with solar panels, O/OrEOS will generate enough power to run its experiments and communicate with ground stations (HAM radio hobbyists can tune in; the satellite broadcasts at 437.305 MHz). Lacking propellant, it includes a mechanism that will push it out of orbit at the end of its mission, causing it to burn up in the upper atmosphere.

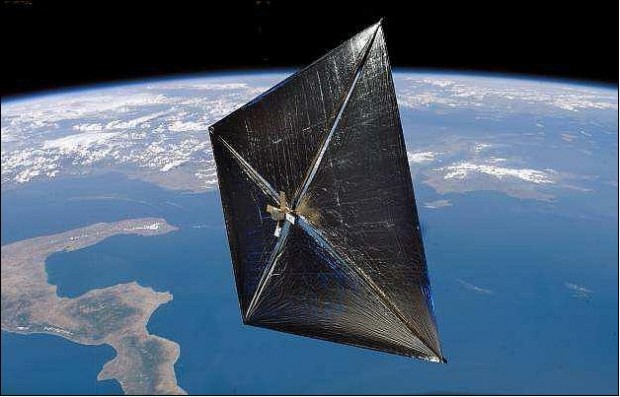

It’s one of a small swarm of seven nanosatellites launched from Alaska aboard a Minotaur 4 rocket last week; another craft, the 4-kilogram NanoSail D2, will unfurl a small solar sail when it deploys on November 27. At about 10 square meters, the solar sail will be too small to test the science-fictional promise of the technology, which many hope will one day power interstellar spacecraft. Its chief purpose is to test the mechanism by which such a sail could be delivered to space rolled up and then sprung open to begin functioning.

Still in their technological infancy, nanosatellites lack the space for pressurization, radiation shielding, and significant power supplies (even tiny Sputnik, which weighed less than two hundred pounds, was large by nanosatellite standards). One day, perhaps, a network of low-powered nanosatellites will advance throughout the solar system?and beyond.

[via Technology Review] Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More